Trust.

It’s the bedrock of every relationship, personal and professional. It’s also integral to ethics. And ethics have been on my mind a lot, since the bombshell revelation about the MIT Media Lab.

Is it just me? I’ve been trying to get my head around how this could happen. Having spent my in-house fundraising career at large organizations – including the Ivory Tower institutions referenced in this mess – I know the extensive research, due diligence, and hyper-attention to both internal and external accountability that are the standard. It should’ve been a given: Ethics is—or at least should be– the core of every fundraiser and every nonprofit executive.

Which is why the arrogance, obfuscation, and greed of the development director and other central development leadership at the heart of the MIT Media Lab scandal angers me. Their recklessness and knowingly unethical behavior brings all fundraisers down.

What happens in the wake of unethical fundraising behavior? It doesn’t just hurt the individuals and institutions directly involved. Trust and credibility suffer for donors and nonprofits across the board. It affects the way donors feel about our sector and make decisions with their resources. It damages the morale and commitment of professionals who serve. It hurts philanthropy’s reputation in the public consciousness.

According to the 2019 Edelman Trust Barometer, trust in the U.S. nonprofit sector is about 52%. Higher than our trust in the government – but, right now, that’s a low bar. And 52% isn’t good enough. We are social change agents. We should be the nation’s most-trusted.

The MIT Media Lab scandal raises the question: Is fundraising at any cost worth it?

We have a crisis in the nonprofit sector.

In the nonstop race to raise higher and higher revenues with fewer and fewer resources, professional development focuses solely on “how to’s” to cross fiscal year finish lines.

It’s a problem only we can fix, and it’s up to every one of us to embrace the importance of ethics as a foundation for our profession.

What lessons can our own organizations learn from the MIT Media Lab scandal?

Consider these questions:

1. Does your nonprofit have clearly-stated guidelines for what types of contributions (and from whom) it will and will not accept?

If “no” or “sort of,” you need to draft a Gift Acceptance Policy or revisit the one you have with your board and leadership. Policies like this define core values for your organization and set parameters (e.g., do you accept artwork, real estate, certain types of securities, etc?). They also explicitly state what kinds of donors your nonprofit won’t deal with (e.g., arms manufacturers, pharmaceutical companies, individuals with certain histories or profiles). In MIT’s case, it’s clear that the Gift Acceptance Policy was ignored by many development and Institute leaders. Not having a policy or disregarding it begs for trouble.

Gift Acceptance Policies articulate who nonprofits want to represent them — whether it’s a board leader or a donor who names something tied to the organization. For pitfalls examples: earlier this year the Whitney Museum faced serious questions and protests by the general public and artists scheduled to exhibit because one of their board members has ties to tear gas manufacturing. Then there are all the museums now wiping their hands clean of the Sackler name after decades of accepting their contributions.

The Gift Acceptance Policy is typically drafted by development staff and discussed with and approved by the board, since they ultimately monitor the accountability of their nonprofit. The policy safeguards reputational and ethical risks, or at least defines what you are willing to sacrifice for a gift. As Helen Brown wrote in a recent blog: If you can defend a company or industry or donor’s alignment with your mission to your stakeholders and the court of public opinion, then you’re good to go. But you need to write it down.

Defining up front your values and terms of gift acceptance builds and reinforces the trust donors can place in you.

2. Does your nonprofit do all it can to bend to your donors’ wishes, even if they violate your ethics or values?

Rogare, a fundraising think tank for whom I was an Advisory Panel member, is doing research on “donor dominance.” The term can feel remote. But it means: In the donor/nonprofit relationship, is there an equal balance of power? Or is the donor exhibiting inappropriate behavior, influence over a nonprofit’s mission, or claiming entitlement to unwarranted benefits and using their gift as leverage?

If you feel that some of your larger donors are expecting too much in return, are wanting to play a role in defining programs or mission, it’s a sign you need a candid and clarifying conversation to reset the donor’s expectations. As a Harvard person, as much as I hate to give Yale credit, they returned a $20 million gift from a long-time benefactor because the donor was placing way too many demands and restrictions on the gift terms. To Yale, it wasn’t worth it.

Again, it’s about trust. When a donor makes a financial contribution, they trust you will put their gift of any amount to good use. They trust that you value them and appreciate their gift, along with all other contributions they receive. If it feels to donors that there’s no room at the table for them, that only those contributing larger sums get attention, they’ll go elsewhere.

3. Do you, your development staff, and board understand how ethics underpins all fundraising?

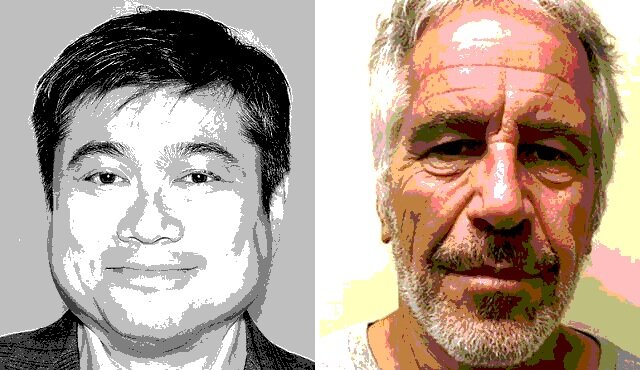

AFP has a Fundraising Code of Ethical Standards. (Quite honestly, I’m not sure most fundraisers know these exist.) It’s why I’m so angry about what happened at the MIT Media Lab. The deliberate unethical behavior to accept and shield Epstein’s money goes against every point of the Ethical Standards to “practice their profession with integrity, honesty, truthfulness and adherence to the absolute obligation to safeguard the public trust.”

Donors trust that the nonprofits they support will live their mission; will use contributions to the best of their organizational ability, honoring the shared intent of social change; and will avoid even the appearance of misconduct and bring credit to the fundraising profession by maintaining the highest standards of accountability.

Along with a Gift Acceptance Policy, your organization needs agreement on ethical standards across all practices.

As my friend and fellow Rogare Advisory Panel member, Heather Hill, CNM, CFRE, put it in her insightful and challenging Chronicle of Philanthropy piece:

When donors lose trust, gifts disappear, and organizations close, will we still think those gifts were worth the cost?

Ethics is as important to your practice and professional development as annual giving and major gifts know-how. Without it, we don’t earn trust.